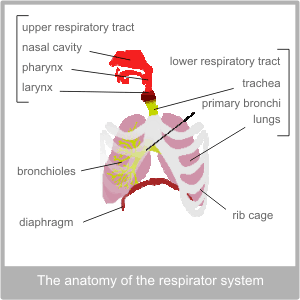

The Anatomy of the Respiratory System

The primary organ of the respiratory system is the lungs, however in conventional terms this system is divided in two: the upper and lower respiratory tracts.

The upper respiratory tract includes, the nose, the nasal cavity, the pharynx, the larynx and the trachea.

The lower respiratory tract begins at the point at which the ‘trunk’ like structure of the trachea splits into the two branches of the bronchi. It includes the bronchi, bronchioles and the lungs.

The lungs are protected by the rib cage. They sit on top of the diaphragm, which is a sheet of muscle. The ribs contain muscles that naturally contract on the out breath.

The lungs are protected by two layers of tissue called, pleura. The pleura secretes a fluid that lubricates the area between them, this facilitates movement. The outside layer of the pleura is attached to the top of the diaphragm and the inside of the ribs. This is what stops the lungs from collapsing.

The Physiology of the Respiratory System

The respiratory system is tasked with two vital roles: supplying the body with oxygen and removing excess carbon dioxide.

The Upper Respiratory Track

The lungs are an extremely delicate organ, but their role requires them to be in constant contact with the air that surrounds us. This means that they are acutely vulnerable to contamination.

Therefore, the main function of the upper respiratory tract is to mitigate this risk. Its primary role is to make sure that the air that reaches deep into the lower respiratory tract is clean, warm and moist. To this end the surface of the respiratory tract is lined with specialised cells. Some of these cells excrete mucus that moistens the air that enters the tract and also catches any foreign bodies as thy pass by. Other cells are topped with tiny hair like structures called cilia, that the cells can control. In the respiratory system all these cilia are constantly ‘wafting’ upwards in order to ferry any contaminated mucus back up the throat where it can be removed. The respiratory tract is also protected by lymphocytes – the immune cells that keep watch for harmful antigens.

The nose and the nasal passages

The nose contains many fine hairs to stop large particles in their tracks. The air, that passes unimpeded, then enters the relatively large, ridged nasal cavity. The size and shape of this space maximises surface area which immediately helps to warm and moisten the air. Theses protective mechanisms explain why it is best to breath in through the nose and not the mouth. The sinuses are small cavities within the bone structure of the face that lead into the nasal cavity. Their role is to give resonance to the voice but because the passages leading to the cavity are small, they can become blocked relatively easily. There is also a drainage system from each eye into the nasal cavity.

The inside of the nose is served by a rich supply of nerves that are adapted both to interpret chemical reactions and also to sense the presence of foreign particles. The first of these aptitudes leads to are ability to smell and the second to the sneeze reflex. The nerves in the nose originate from the base of the brain. It is thought that smell is the most ancient of all our senses.

The pharynx

The pharynx is the name given to the space that connects the end of the nose with the throat. It is lined either side with two sets of tonsils. One set which we usually refer to as the adenoids is actually at the back of the nose, high enough up to be out of view. The other pair can usually be seen at the back of the throat. Tonsils are made up of lymphoid tissue and their role is to stand sentinel for the immune system, protecting the lungs from invades. As with the eyes into the nasal cavity, the ears have a drainage route into the pharynx. This is called the eustachian tube.

The larynx

The larynx is also known as the voice box. Physically, it separates the pharynx from the trachea and is situated under the ‘Adam’s apple’. Essentially, the voice box works because the structure of the larynx is a fixed shape. Attached to this structure are fine sheets of tissue, known as the vocal cords. These can be manipulated by muscle control to produce sound – much like guitar strings. The tighter the cords are (and the smaller the space between them) the higher the pitch of sound produced.

As humans, we have harnessed this mechanism to produce the extremely useful skill of communication, but it does also have another purpose. If something needs to be removed from the lungs we can breathe in and then close the flaps of the vocal cords as we breathe out. This builds up the pressure in the throat and when the cords are finally opened – we cough.

To protect us from accidentally taking food and drink into the lungs there is another structure in the larynx called the epiglottis. This flap of cartilage acts like a door that closes off the voice box when we swallow.

The trachea

This is the wide tube that descends into the chest towards the lungs. Like the larynx it is made of stiff cartilage which means that it is held open like a pipe.